The Naming of Edinburgh

The Naming of Edinburgh

(a guide to pronunciation

of Celtic / Saxon names is at App 1)

After the Roman occupation of the Lothians

between 140 and 163ad, the region was left mainly to its Celtic inhabitants.

The Romans had named them Votadini, but they called themselves Gododdin.

They had settled mainly in hill-forts, which were good protective vantage

points. Their chief settlement was east of present day Haddington, at Traprain

Law, home of the legendary King Loth, who gave his name to the region.

However, with the passing of centuries, the

focus of their tribal life shifted westward to a prominent volcanic plug and

tail to the north of the imposing Pentland range, lying astride the gently

sloping hills running down to the shores of the Firth of Forth; this they came

to know as Dyn Eidyn, the fort on a hill-slope. The sound of the name is

Celtic, without doubt, and parallels the modern Scots Gaelic name of the city,

Dun Eideann. However, the language of the Gododdin was Brythonic,

more like Welsh or Cornish than Gaelic.

The transition of Edinburgh from a pagan,

Celtic stronghold to a Saxon, Christian settlement is difficult to outline with

absolute certainty. However, there are some clear pointers, which explain to us

how it comes today to be called Edinburgh, rather than Dunedin .

Towards the end of the sixth century, possibly

between 590ad and 600ad, the Gododdin, under their King Mynyddawg Mwynfawr,

suffered a stinging defeat at the hands of the Saxons of the newly united

kingdom of Northumbria. For up to a year before their decisive encounter, the

Gododdin enjoyed being feted and banqueted by King Mynyddawg, perhaps realising

that their days were numbered.

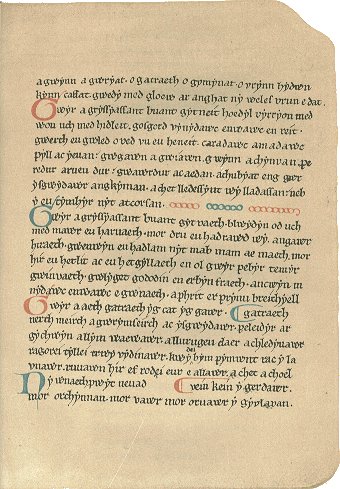

In the earliest extant Welsh poem, Y

Gododdin, written by the bard Aneirin, somewhere around Edinburgh at the

end of the sixth century, we read of this feasting , followed by devastating

defeat, here in English translation.

From the banquet of wine and mead they hastened,

Men renowned in difficulty, careless of their lives;

In bright array around the viands they feasted together;

Wine and mead and meal they enjoyed.

From the retinue of Mynyddawg I am being ruined;

And I have lost a leader from among my true friends.

Of the body of three hundred men that hastened to Catraeth,

Alas ! None have returned but one alone…

Page from the Book of Aneirin >>

Catraeth in the Welsh is possibly Catterick, in Yorkshire, a significant settlement in those times. The Gododdin retreated to Lothian, and began their descent into obscurity.

It is here that Edinburgh's namesake first

makes his entrance. Prince Edwin was the son of Ælla, deceased King of Deira,

and next in line to his throne. When Æthelric, Æthelfrith's father, had wrested

the Kingdom from him, Edwin was only four years old; he was taken to safety,

and began a long exile for the next quarter century among the Anglo-Saxon kings

of the south.

Eventually, with the help of Rædwald of East

Anglia, Edwin rode north in 616ad. Æthelfrith was unprepared, and was roundly

defeated at the Battle of the River Idle, near Doncaster, losing his life in

the attack . Now it was Æthelfrith's heirs, Eanfrith, Oswald and Oswiu, with

their sister Ebba who sought refuge from an avenging army. The latter three

came eventually to the island of Iona, at that time part of the Scottish

Kingdom of Dalriada; here they were shielded and educated by Christian monks in

the monastery Columba had established half a century before. Their brother,

Eanfrith, however, found refuge among the now diminished Gododdin in Lothian.

Edwin was victorious, aged thirty-two. His

Queen, Cwenburh having either died, or been 'put away' by divorce, in 625ad,

Edwin sent to ask King Eadbald of Kent for the hand of his daughter, Æthelburh,

in marriage. Eadbald was unwilling, for Kent had received Christian baptism,

through the mission of Augustine to Canterbury in 597ad, and he was afraid lest

his daughter should be defiled by a pagan King. Edwin responded by assuring the

Kentish ruler that his daughter should be allowed every freedom to worship as she

wished, and he would even consider converting himself, if he found her faith

more attractive and preferable.

Paulinus her priest, in the years after their

marriage, conducted a gentle ministry of persuasion of the King to follow

Christ. Eventually, in 627ad, Edwin was almost ready to surrender his life to

the King of Kings, but first, he wanted to consult his counsellors and friends.

Bede tells us of Edwin's pagan priest, Cefi,

whose testimony to the King is that , as his priest, he has been the most devoted

of all men in his observance of the rituals and requirements of the gods. Yet

he has never seen that it does any good, and is willing to give up the old ways

for Christ. Cefi then goes on to be the first to desecrate the pagan shrines,

taking a sword and riding a stallion, both of which the old religion forbade

him to do, hastening to cast a desecrating spear into the temples of the gods,

at Goodmanham, in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Paulinus duly baptised Edwin and his thegns on Easter Day,

April 12th 627ad, in the church of St Peter in York, which the King

had built while he was preparing for the ceremony as a catechumen.

Paulinus duly baptised Edwin and his thegns on Easter Day,

April 12th 627ad, in the church of St Peter in York, which the King

had built while he was preparing for the ceremony as a catechumen.

Edwin continued his reign, then, as the first

Christian King of Northumbria; Paulinus preached far and wide, baptising many,

for example, in the River Glen, near the King's northern palace of Yeavering,

near present day Wooler, as well as in the River Swale near Catterick.

<< York Minster, built on the site of

St Peter's, Edwin's First Church

This, then, is the King for whom Edinburgh is

named. But how does a Saxon King come to have his name given to a Celtic city ?

Within a few years, Edwin had made himself

powerful enemies through his efforts to extend his influence as far as Anglesey

and the Isle of Man. Allied with Penda of Mercia, Cadwallon of Gwynedd raised

an army against him, and at the Battle of Hatfield Chase, to the north of

London, Edwin was slain in 633ad. His family fled to Kent, to Æthelburh's

relations. He was buried, his body at Whitby, and his head at York. He was later

declared a saint of the church, his death being seen as a martyrdom, although

he is not given a feast day in the calendar.

Now the forces of paganism reasserted

themselves; dividing again the Northumbrian territories, for a year Edwin's

cousin, Osric, assumed the throne of Deira, while Eanfrith, Æthelfrith's son,

seized power in northern Bernicia, coming out of his hiding among the Picts.

For the church, it was a devastating blow. Paulinus retreated with the widowed

Queen, back to the safety of Canterbury. The two kings of the north abjured

their faith and returned to Woden-worship. So bad was it, that Bede in his

history refused to count it as a year at all.

Within a few months, however, Cadwallon of

Gwynedd had despatched both the new rulers, Osric being slain during a failed

siege in Wales, and Eanfrith, killed when he came to sue for peace. Thus the

Britons were holding Northumbria.

Now, a new hope emerged for

The following year, after one failed attempt to find an

evangelist from Iona to preach to his wayward peoples, Oswald received Aidan at

his capital of Bebbanburgh (now Bamburgh), granting to him the island Aidan

called Innis Medcaut, known to Oswald as Lindisfarne. Here, the abbey which was

later celebrated as the Cradle of English Christianity was established. Aidan,

a Gael, had no English when he came, and so he would preach, the devoted King

translating for him the message of eternal life to his thegns and his people.

<< The Holy Island of

But on Oswald's northern borders still were

ensconced the British tribe of the Gododdin. Whether he saw them as a military

threat, or whether he wanted to bring them into the Christian fold, in 638ad,

Oswald besieged Dyn Eidyn, and captured it, establishing Northumbrian rule

there, and bringing to an end the British chapter in its story. And the place

remained in the Saxon's domain for the next three centuries, never losing its

Northumbrian character, so that it became the favoured retreat in the first century

of the next millennium of Malcolm of Scotland's Saxon-Hungarian Queen,

Margaret, who, with their sons, Edgar, Alexander and David, did so much to

establish it as the cultural heart of Scotland.

<< 7th century

Northumbrian Cross-Shaft from Abercorn, near Edinburgh

It is perhaps a Divine irony that Oswald, the

Christian King driven from his homeland by a rival claimant, should honour that

same rival by baptising the newly taken fortress with his name, Edwinesburg.

Thus Edinburgh was changed forever. Perhaps Oswald saw a divine portent in the

similarity of the Celtic Eidyn with the King's name he had given to it. But

Oswald himself was a fusion of Saxon and Celt, through his upbringing on Iona,

and it was Columba's rite, not Rome's, through which the new faith was mediated

to the people of Lothian.

There is no evidence that Aidan came to

evangelise this newly acquired territory; that honour is usually accorded

Cuthbert, whose call to Christ was inspired by a vision of Aidan's ascent to

heaven. But it is not beyond the realms of possibility to imagine Bishop and

King preaching to the people in the villages and hamlets up and down the

forested slopes which now formed the northern borders of Oswald's kingdom, the

Gael and the Saxon together bringing Christ's Word to the future city, now

named for the King who had led the Northumbrians to the feet of Jesus Christ,

and whose priest himself destroyed the discredited and unfruitful trappings of

paganism .

Colin Symes

Edinburgh 28 March 2003

References

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English

People

Aneirin, Y Gododdin

The Annals of Ulster ( 638 )

Appendix 1; Notes on Pronunciation

Ælla, as Ella (Old English Æ is, however, a

more open sound than modern English E)

Æthelburh , as Ethelboorch ('th'

voiced, ch as in Scots loch)

Æthelfrith, as Ethelfrith ( first 'th'

voiced, second unvoiced)

Æthelric , as Ethelrick ('th' voiced)

Cefi as Kevi

Cwenburh as Quenboorch (ch as in

Scots loch)

Dyn Eidyn, as Din Eddin

Mynyddawg Mwynfawr, pronounced as Mini-thowg

Mwin-vower ('th' voiced)

Rædwald as Radwald

Thegn, as thane

Y Gododdin as ee Godothin ('th' voiced)